Custom Motorcyclists Fully Embrace the Art of the Wheel

By Neely Tucker

Washington Post Staff Writer

Saturday, January 10, 2009; Page C01

Somewhere out there on the American road is a motorcycle like no other.

Somewhere out there is a two-wheeled machine so unique, so frightfully original, that you could never find another like it.

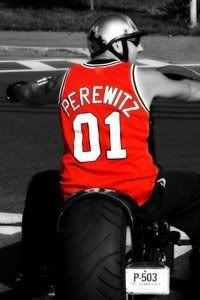

Custom motorcycles are riding the crest of motorhead machismo, the thingy to get for boys about 45 who have $20,000 and up to plunk down for something that they'll drive a few dozen times a year. You can find guys making one-of-a-kind motorcycles -- forget a Harley! Never mind the Ducati! -- from Baton Rouge to Bangor. It's "American Chopper," it's West Coast Choppers, it's Will Smith and Kid Rock and John Elway tooling around on two wheels of motorized art, it's genre founders like Dave Perewitz, it's guys who fork out for an avatar that no one else will ever have.

Here's Alfredo Carlini, 40-something, chopper-maker extraordinaire, getting his Hardcore Choppers in Sterling ready for the Cycle World International Motorcycle Show at the Walter E. Washington Convention Center this weekend.

"Art is the experience of you, and since we're all unique, that's not so much," he says, talking in his workshop, buried in an industrial and office park near Dulles Airport. "But craftsmanship! That's a discipline. Not everyone can do that. That's what custom motorcycles are -- craft."

Carlini will be showing off seven or eight highly stylized bikes at the show this weekend -- crazy things with the front wheel about a mile from the cycle body. He machines his own parts; he builds bikes with names. High Life. Beef Cake. Urban Assault Chopper. Makes about 75 bikes a year, has a staff of 10. Sells across the United States, Europe, the Mideast, South America. He can make you a simple bobber, those 1950s-looking things, starting at $16,000. Most are double that. One went for $200,000.

"These are not impulse buys. These are toys these guys have been thinking about for years," he says.

Will Langhorne, D.C. area native and international race car driver, knew he wanted a custom bike. He also knew whom he wanted to build it.

"Alfredo is really doing unique things," says Langhorne, who owns the aforementioned Urban Assault and is working with Carlini on another bike. "Really pushing the envelope."

Custom bikes used to be outre, in a garage-punk kind of way. They were down-market and kind of weird. It started just after World War II, when returning soldiers started stripping down production bikes -- then as now mostly Harley-Davidsons -- to get a different, wilder look. You pared the bike down, "chopped" off the fenders or fairing or anything else. High handlebars, the low seat, the raised foot pegs up front -- these were standard modifications.

"I remember making bikes back in the 1970s, and I might be able to sell one for $5,000," says Perewitz, the Massachusetts-based builder who is a legend in the field. (He now builds only a dozen a year. They start at $60,000.) "There was only me and a few guys across the country who did it. We all knew each other."

Carlini likes to call his bikes "hard-core Americana" to reflect that tradition.

But with computer engineering making original parts easier and cheaper to manufacture, and cable shows such as "American Chopper" gaining a large audience, one-of-a-kind bikes have become . . . mainstream. Paul Teutul Sr., the mustachioed star of "Chopper," says in a telephone interview that though the show has boosted the demand for his motorcycles, what everyone really wanted was the T-shirts.

"It was the merchandising we couldn't keep up with," he says.

But as American builders made more money, their designs lagged. At the six-year-old AMD World Championship of Custom Bike Building -- held in your red-white-and-blue bastion of Sturgis, S.D. -- no American designer has ever won. Canada, yes. Japan, yes. Sweden (Sweden!), yes. 'Murcans? Nope.

"Things in the United States just stopped evolving in the late 1990s," says Robin Bradley, founder of American Motorcycle Dealer magazine and creator of the contest. "They kept referring to [motorcycle styles] in the 1950s and 1960s. It was very popular, and there's nothing wrong with it as a business model. But stylistically, creatively, the rest of the world moved on."

Carlini doesn't go for high-profile. He grew up in Springfield. Went to George Mason. Did four years in the Army. Ran a body shop. Put together his first bike in 1991, just for himself. Drove it up to the gas station to fill up -- guy offers to buy it. Opened his own place five years later.

Today, the only external sign that the place exists is a black and red banner atop the two-story building. The banner is partly torn by the wind. You have to be buzzed in. There's no real showroom. There are old carpets and tires and cardboard boxes of parts on the floor. Only one of the two fluorescent overhead lights is working in his office. It's as drab as the bikes are fiercely beautiful.

A little bit of America, the heart still beating.